A Grandfather’s Gift to a Grandson He Never Met

“Who has fully realized that history is not contained in thick books but lives in our very blood?” — Carl Jung

Visiting America

As my family tells it, his face—with its defined lines grooved by dirt, strife and time—held a solemn look most days. Weary or apathy was not the matter, it was a face well worn. A face having spent time in his village watching the nearby river slowly dismantle the fading banks. Even with all those years between him and the war, it was a face etched with wrinkles wrought by the tears he could no longer shed. Anymore, his mood would shift only after dinner.

“I’m going to America today,” he’d declare. Taking out his faux leather-bound album, grandfather would chuckle as he opened to the first page. The photographs were slightly crinkled having sat beneath cracked yellowing plastic covers for some years. But that didn’t matter. The true treasure were the faces sitting behind those sheets.

The smile would appear slowly at first. As pages turned, the creases in his brow and on his cheeks would stretch taut, crevices giving way to delight.

“Look at that!” he would shout slapping his fingers onto the photos. Then he would smoothen the photographs with those fingers, fingers well aged in setting bones, mixing herbs, punching posts and pulling triggers. “That’s my grandson!” he’d proclaim, as if sharing the images to the family for the first time.

My grandmother told me that during those span of years in their lives, this was the only time my grandfather really showed any emotion. The war and reeducation had wrested the rest away from him. What brought him life were his memories.

And that album.

Across the Seas

The world in which you were born is just one model of reality. Other cultures are not failed attempts at being you; they are unique manifestations of the human spirit. ― Wade Davis

Those were the early 90s. Telecommunications were much different then, strikingly so when considering the gaps between the Vietnam countryside and Philadelphian suburb. Phone calls were scheduled months in advanced by handwritten postal mail. A time was arranged and the family in Ang Giang would travel to the designated phone station where the phone sat. When the phone rang, they would answer. And we’d be on the other side waiting for a “Hello?”

At this point in my life I had never met my extended family. Beyond the perimeter of my parents and sister, the rest of my kin were all abstract ideas inferred by stories and brief phone conversations during special holidays.

I remember the last phone conversation I would share with my grandfather. I no longer remember the sound of his voice, nor exactly what we talked about, but vividly recall the setting that January evening.

Our lights were off. It was early. My sister and I were already asleep, but our parents woke us up in the dark dawn to call the family. With the 12-hour difference, our uncles and aunts would be back from their day’s work.

I still remember sitting on the shag carpet watching my mother with the cordless phone pressed firmly against her ear. In two weeks time it would be the Lunar New Year and my mother was excited to talk about some final plans before she would touch Vietnam soil for the first time in 15 years.

I remember her talking to the family as I rubbed my eyes, head rested on the couch with arms slung over the side. I wanted a chance to talk to grandpa and grandma. I wanted to hear their voices. My mother handed me the grey magical box that would send me to my family a whole world away. And we talked.

I can remember pacing the room, chirping excitedly. And then we said our goodbyes as I passed the phone along to my sister. And that was the last time I heard my grandfather’s voice. A week later he passed away.

Verbal History

There was no wealth after the war and so there were no heirlooms to pass on, no tokens, no mementos. All we had were the memories. All I had were the phone calls made 12,000 miles apart. And our stories. For a time, all we had were our stories.

Those stories and what they inspired became the only links left between me and my grandfather. Some were loving, others humorous, a few fantastical and others still, curious. My favorites were always the gung fu adventures involving my grandfather, his teacher and a mysterious man by the name of Ong Dao Luong. (While amongst my favorite stories, Ong Dao Luong will have to wait for another time.)

Hearing my grandfather taught gung fu in those days—that he, in fact, practiced in a familial style tied to our heritage—grabbed my imagination early in my post-toddler life. Vo Lam it was called, a general term for a variety of indigenous combat arts. Despite the lack of specificity in name, his art was his and therefore it was something worth exploring.

Grandfather would wake my mother up in the early mornings to practice in the predawn light. Atop the roof of their three-story home, he forged her through the skills of our family’s art.

I wanted to learn gung fu like my mother had. I wanted to practice with my grandfather. But at this point in my life, my mother didn’t remember much of what she had learned. That was so long ago, further distanced by other worldly trials and concerns. She was, however, able to recall a few movements from grandfather’s routine called “Man Ho Li Son”–Mighty Tiger Up The Golden Mountain. And while my martial arts journey blossomed in other ways, it was with those movements I first felt aspiration, an undying passion for a particular kind of cultural movement. Here was where I began to learn, not only my grandfather’s legacy, but also his secret in visiting loved ones so far away.

A civilization is a heritage of beliefs, customs, and knowledge slowly accumulated in the course of centuries, elements difficult at times to justify by logic, but justifying themselves as paths when they lead somewhere, since they open up for man his inner distance. — Antoine de Saint-Exupery

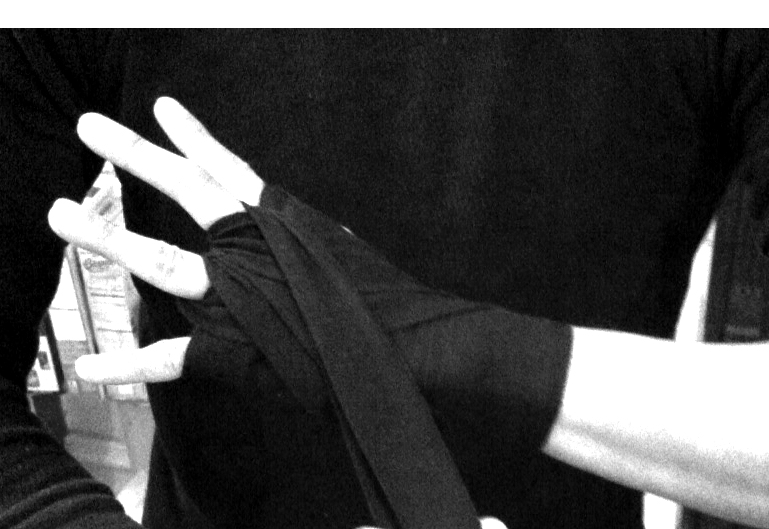

I spent the next years of my life asking my mother to retell me stories of my grandfather’s training, of his skills and of his personality. I dove into various styles of gung fu, boxing and MMA for the next 20 years of my life. In my early twenties I traveled back to Vietnam, to my uncles, aunts, great uncles and neighbors seeking nuggets of information about my grandfather. To discover how he interacted with people, what motivated him, the intricacies of his life and the peculiarities of his movements. With the help of loved ones I pieced together the aforementioned Man Ho Li Son in its entirety. My great uncle, a contemporary with my grandfather, attempted to show me applications and concepts he learned alongside his friend. The years prior spent refining other martial arts informed my practice with the new aspects I encountered from my grandfather’s art.

Fast forward four years. I met with another extended family member who recalled techniques and three additional forms. With a friend, I recorded this knowledge on video while dedicating a day practicing the forms, to not only document them digitally, but also commit them biomechanically. By day’s end, I received the physio-textbooks of my grandfather’s art, regardless of how patchwork the process, how piecemeal the research.

Inheritance

There are aspects of gung fu and martial arts similar to dancing. But whereas there is generally a large level of cooperation in dance (there are certainly exceptions), communicating through martial arts offers more opportunity for abrupt randomization. While also requiring a level of cooperation and understanding, moments in martial arts provide plenty more instances of disruptive pulse-like exchanges. Many times, the purpose is to outsmart and out maneuver your friend, albeit in the hopes that your friend counters, returning the favor to you. It is communication on the level of a chess match—through feinting, counters and attacks. You not only learn your opponent’s or partner’s physicality, but also their mentality, personality and creativity. An exchange between martial artists can be made with anger and aggression or with amicability and admiration. Like life, communicating with martial arts has layers.

But how do you communicate in that way with a grandfather who passed before you met him? You can’t. But you can catch a glimpse of what it may have been like to do so by practicing the routines he practiced. By extrapolating the techniques from those routines. By contemplating what he would have suggested when you considered the relevance of using those techniques in exchanges with contemporary martial artists.

There is a concept of design called heritage design. It is the idea that in today’s planned obsolescence, in our daily items’ inherent devaluing over time due to the nature in which technology rapidly progresses, we should begin to again design things meant to last. Not simply lasting in our lifetimes, but creating things so well crafted they last generations. Designing family heirlooms.

These stories and the very tangible experiences of performing choreographed routines established by my grandfather, these are my inheritance. It is difficult to describe to someone who hasn’t had the isolation from family, who doesn’t desperately seek out glimpses of his past, it is difficult to describe how much this all means. For me, performing these movements are something very special, knowing that I am not simply reading a piece of history through which my grandfather lived, but for a moment in time and space performing the very movements he did, experiencing the same twist, turn and tumble of my limbs as he had. This experience, this art, my grandfather’s gift is my photo album. This art is a very sacred thing to me and it is through this art that I visit my grandfather

Some people are your relatives but others are your ancestors, and you choose the ones you want to have as ancestors. You create yourself out of those values. — Ralph Ellison

You see, I was never handed an oil-worn baseball glove, or precisely tuned watch. No one would want to sell their grandfather’s old timepiece; I wouldn’t want to sell my grandfather’s gung fu. What was gifted me was deeper than a simple bit of nostalgia. I was given a way of communicating cultural value and heritage within the mediums of story and practice, bonding me beyond land, ocean, time and death itself. My grandfather lives on because I dream of him, think to him and practice the things he cherished. For a moment in time, my grandfather visited my family through his photo album. For a moment in time, I visit my grandfather when performing those movements he performed all those years ago.

During those moments in time, he lives on.